Te Noho Kotahitanga, the marae at Unitec, was officially opened on Friday 13 March 2009, in front of more than 1,000 people — a historic milestone that marked a significant commitment to bicultural partnership and the Treaty of Waitangi.

Rooted in the partnership document Te Noho Kotahitanga (established in 2001), the marae symbolises Unitec’s dedication to advancing a Māori dimension in teaching and research. It stands as a space for learning, cultural exchange, and community connection, reflecting the aspirations of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

A Place for All

Te Noho Kotahitanga is more than a physical space — it is a place of inclusion, comfort, and cultural engagement. It serves all Unitec staff and students through pōwhiri, noho marae (overnight stays), hui, and workshops. As a hub for te ao Māori, it offers inspiring Mātauranga Māori electives exploring te reo, tikanga, Māori philosophy, cosmology, and traditional arts like tā moko and raranga.

A Masterpiece in Design

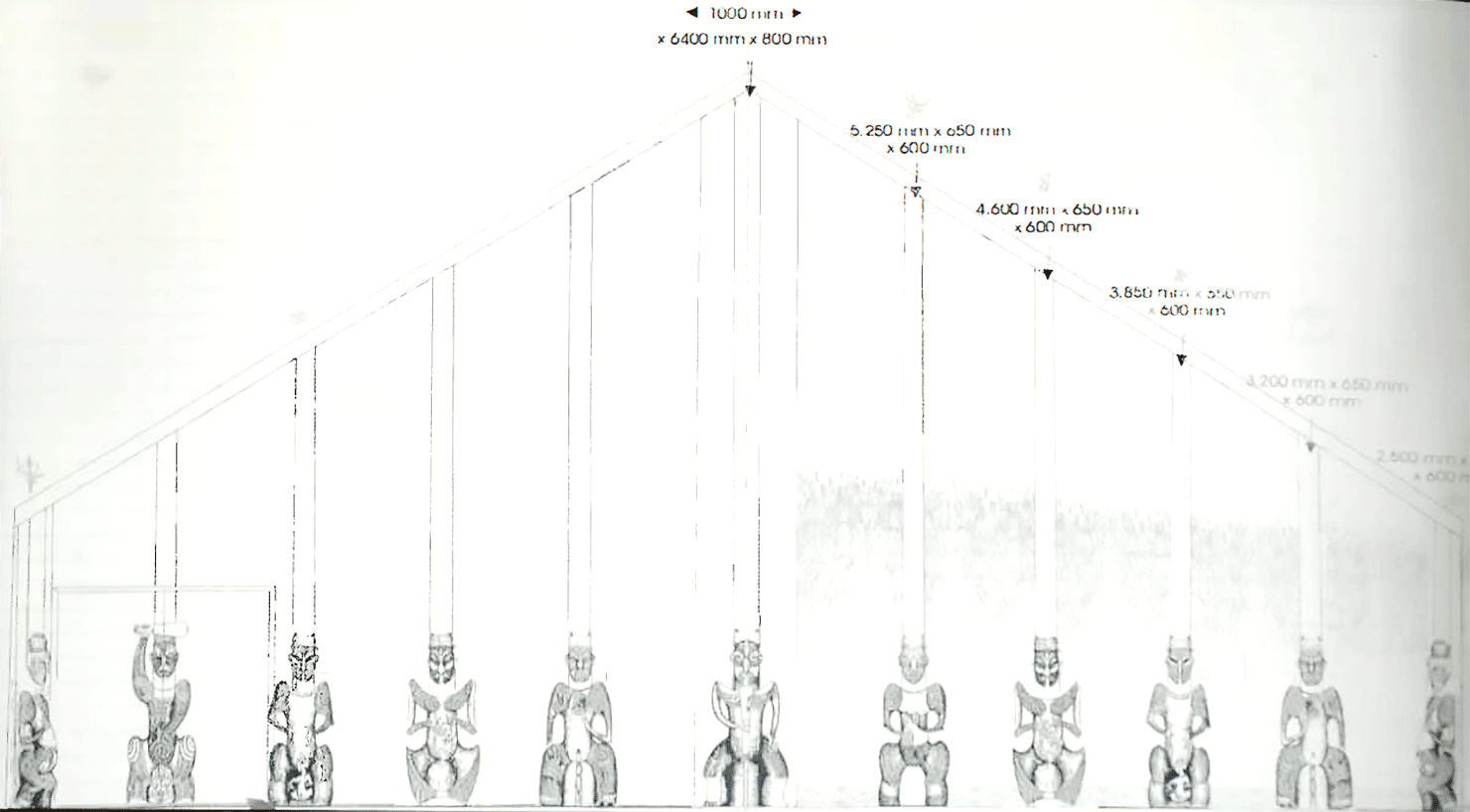

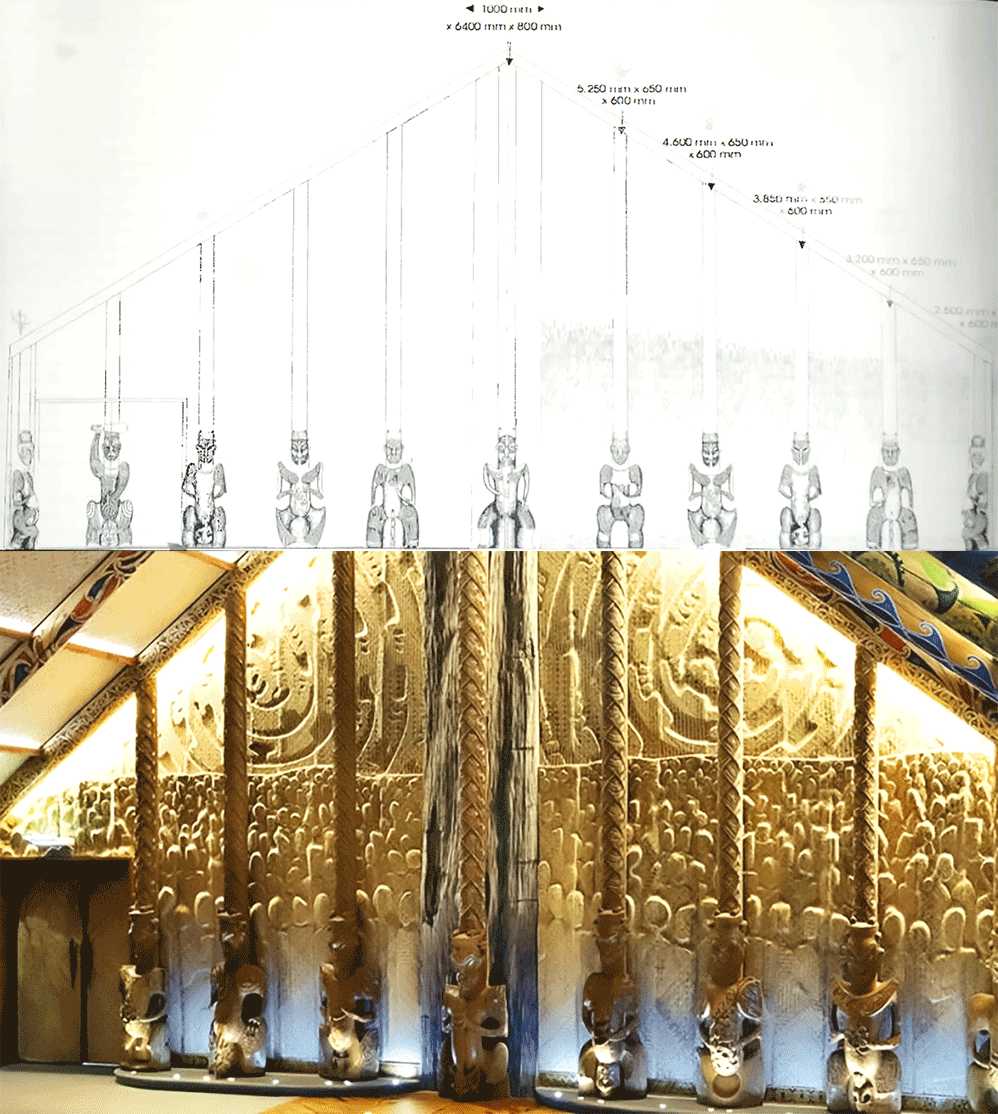

At the heart of the marae is the wharenui — a traditional whare whakairo (carved meeting house) brought to life through the vision of master carver Lyonel Grant. As Lyonel’s third and most ambitious project, the wharenui revives centuries-old techniques while innovating for the future.

Constructed in the traditional fashion, the structure relies on carved elements for support — not a single nail was used. This method contrasts with modern practice and demonstrates Lyonel’s commitment to structural and artistic integrity.

A Story Told in Every Detail

Everything within the wharenui carries meaning. The carvings, weaving, and layout represent a timeline from the beginning of time (back wall) to the present day (front wall), with the central poutokomanawa (heart post) marking the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840.

The front interior wall features a carved map of Auckland, designed to reveal the layered history of Tāmaki Makaurau — Mt Albert, Pt Chevalier, Waterview, and Carrington.

The tāhuhu (ridgepole), representing ancestral backbone, is formed by four traditional waka lashings.

Carvings reinterpret traditional forms with modern influences — for example, a poupou depicting a warrior with a broken gun refers to Hongi Hika and the era of muskets and changing iwi relations.

Another poupou honours Ruarangi, a Tūrehu ancestor connected to the lava caves of Ōwairaka.

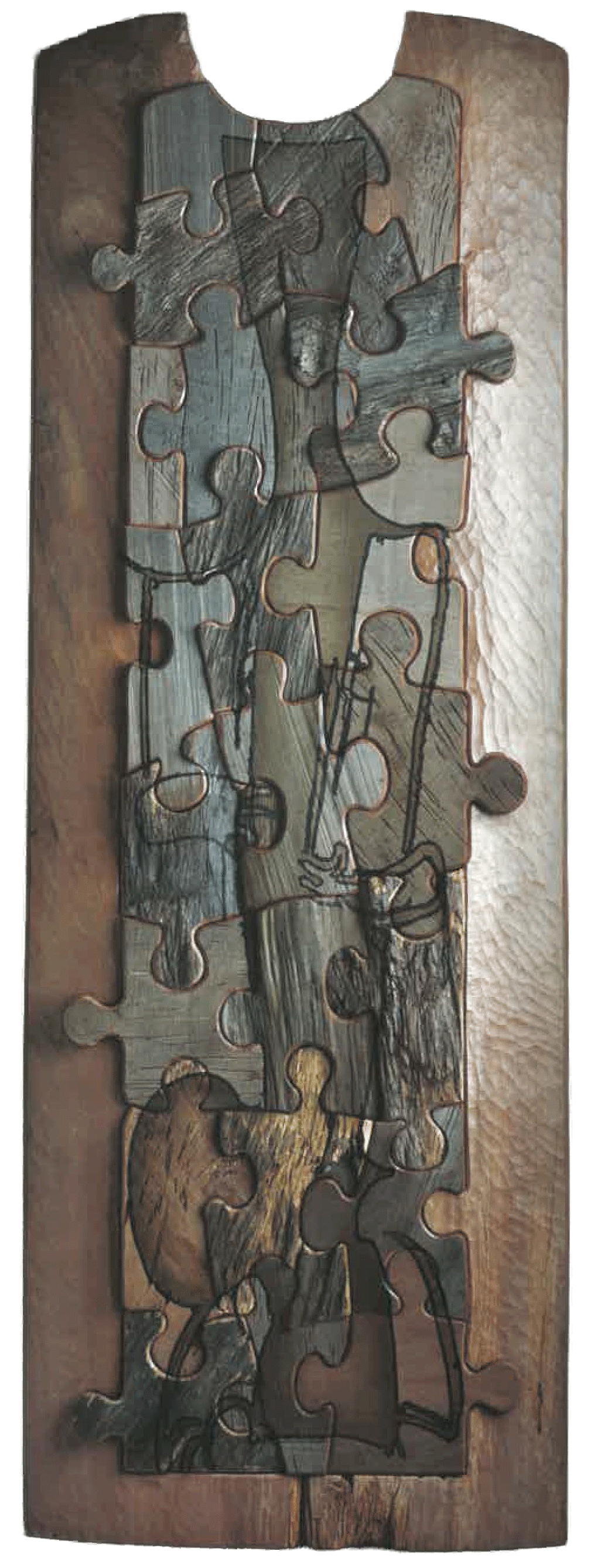

One poupou, left uncarved, symbolises the Heruiwi block — the land in the Whirinaki Forest where Ngāti Manawa and Ngāti Whare gifted logs for the wharenui. This piece marks a time of conservation and change in Aotearoa’s environmental history.

The back wall features 11 carved figures set against an arai (veil) of woven and wooden panels, separating the spiritual and physical worlds. In formal oratory, this veil signifies the journey beyond — kua haere rātou ki tua o te arai — rooting the space in ancestral wisdom and the present.

Weaving the Past and Present

Nearly 28,000 flax strips make up the back wall weaving — originally prepared by four weavers and completed by two, with guidance from Kahu Te Kanawa and Judy Hohaia. Each woven piece, including student and community contributions between poupou, adds layers of shared identity.

The front wall’s layered weaving mimics the sea, a reminder of the journeys, migrations, and stories that bind people to place.

Te Noho Kotahitanga is not just a marae. It is a living legacy — a place where heritage and innovation meet, where the stories of Tāmaki Makaurau and its people are carved, woven, and remembered.